HH Cox

HH COX, JR. (US ARMY), Canton, Texas

HH Cox was born in Kaufman, Texas on January 3rd of 1923. He had two brothers William and Robert and two sisters Margie and Elsie. HH was the oldest child and was considered a mommas boy. Henry Homer, was his dad’s name and he served as an Infantryman in the Army. “My dad and his stepbrother served in World War I.

Dad did not talk about the war and when I signed up for the Army he knew what I was getting into,” said HH. “I would ask him about the war, but he would always answer by saying, “I would rather not tell you.” “I had five sons and that was my answer to them,” said HH.

His mother’s name was Elsie. She stayed at home raising the five kids and did a lot of canning and other chores around the house.

“I grew up on the farm and we had some acreage,” said HH. “We had one hundred and sixty acres. We raised cotton, corn and some vegetables. My dad raised about ten cows and a few hogs. We sold the cotton and corn to the market. We started off using two mules named Colley and Mary. They pulled the plow so we could till the acreage. I only made it thru the 8th grade in school in Kaufman.

Getting Married at 16

“When did you get married?” I asked. “I was married before I went overseas,” said HH. “I got married in 1939, I was 16 years old. I picked her up in my school class. Her name was Hazel. It was love at 2nd sight. I didn’t like her on first sight, I guess. We were all out with several other friends and I asked her if I could walk home with her from a party. She said, you would have to ask my brother. He said yes, and one year later we were married. What did you love about her? I asked. Well maybe I can say this the right way or maybe I can say it the wrong way. She was smart enough to head me in the right direction. I would ask her a crazy question, and she would come back with a crazy answer. She had a good sense of humor. We were married for 47 years. She passed away in 1986,” recalled HH.

“Red headed and brown eyes,” chimed in his daughter Lettie.

Joining the Military

“I was drafted into the Army when I was 21 years old. I was working for a friend of my dad’s name Jack Mowery on his farm. I moved out of my parent’s home and moved in with Jack. He had a large farm. I remember it was over a thousand acres. He was the “Ramrod” or overseer of the farm. At some point he had as many as twelve people working under him on the farm.

There was a lot of talk coming out of Europe and the war that was raging. I felt like eventually I was going to be drafted. The draft did finally catch up to me and I was drafted into the Army on December 1st 1944,” he said.

HH went to boot camp on the 24th of December 1944 at Ft. Hood, Texas. It was close enough that I was able to make it home on the weekends. I was in boot for seventeen weeks graduating on April 6, 1945. Having worked on the farm bailing hay and picking cotton the physical part was pretty easy for me in Boot Camp,” laughed HH.

He was sent to Ft. Mead Maryland for Infantry training. After training HH took a train to San Francisco and boarded a ship overseas and stopped for fuel at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

HH recalls standing on the side of the ship looking out over the harbor and all the devastation.

“I saw a whole bunch of ships sunk at Pearl Harbor. There was destruction everywhere. It made you want to get after somebody. We have a job to do now let’s go over and do it,” said HH. “I am 97 years old but I still remember that day and what Pearl Harbor looked like.”

It had been three years since the attack by the Japanese. He was ready to go to the Philippines and kill the people who did this to his country.

He quickly saw battle at the Battle of Manilla as an infantryman in the 3rd Battalion 63rd Infantry. He was a chauffeur (345) in Luzon while fighting in the Philippines.

The Invasion and Battle for Luzon

Ultimately ten U.S. divisions and five independent regiments would see action on Luzon, making it the largest campaign of the Pacific war and involving more troops in any invasion than the United States had used in North Africa, Italy, or southern France.

The weather on 9 January (called S-day) was ideal. A light overcast dappled the predawn sky, and gentle waves promised a smooth ride onto the beach. At 0700 the pre assault bombardment began and was followed an hour later by the landings.

With little initial Japanese opposition, General Krueger’s Sixth Army landed almost 175,000 men along a twenty-mile beachhead within a few days. While the I Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Innis P. Swift, protected the beachhead’s flanks, Lt. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold’s XIV Corps prepared to drive south, first to Clark Field and then to Manila. Only after the Manila area had been secured was Swift’s I Corps to push north and east to seize the vital road junctions leading from the coast into the mountains of northern Luzon.

American casualties were also high. Ground combat losses for the Sixth and Eighth Armies were almost 47,000, some 10,380 killed and 36,550 wounded. Non-battle casualties were even heavier. From 9 January through 30 June 1945, the Sixth Army on Luzon suffered 93,422 non-combat casualties, including 260 deaths, most of them from disease. During that same period, the battle casualties for the 6th Army, alone, totaled 37,854 of which 8,140 were killed in action. Only a few campaigns had a higher casualty rate.

The largest American Battle Monument Commission Cometary outside of Arlington Virginia, is on Luzon where over 17,000 Americans are buried. Courtesy: 6thinfantry.com

On 15 December 1944, landings against minimal resistance were made on the southern beaches of the island of Mindoro, a key location in the planned Lingayen Gulf operations, in support of major landings scheduled on Luzon. On 9 January 1945, on the south shore of Lingayen Gulf on the western coast of Luzon, General Krueger’s Sixth Army landed his first units.

Almost 175,000 men followed across the twenty-mile beachhead within a few days. With heavy air support, Army units pushed inland, taking Clark Field, 40 miles northwest of Manila, in the last week of January.

Two more major landings followed, one to cut off the Bataan Peninsula, and another, that included a parachute drop, south of Manila. Pincers closed on the city and, on 3 February 1945, elements of the 1st Cavalry Division pushed into the northern outskirts of Manila and the 8th Cavalry passed through the northern suburbs and into the city itself.

As the advance on Manila continued from the north and the south, the Bataan Peninsula was rapidly secured. On 16 February, paratroopers and amphibious units assaulted Corregidor, and resistance ended there on 27 February.

Despite initial optimism, fighting in Manila was harsh. It took until 3 March to clear the city of all Japanese troops. Fort Drum, a fortified island in Manila Bay near Corregidor, held out until 13 April, when a team went ashore and pumped 3,000 gallons of diesel fuel into the fort, then set charges. No Japanese survived the blast and fire. In all, ten U.S. divisions and five independent regiments battled on Luzon, making it the largest campaign of the Pacific war, involving more troops than the United States had used in North Africa, Italy, or southern France. www.worldwarphotos.info.

“There were a lot of “Gook” kids no bigger than that,” he said. “You pom pom mama, you pom pom mama they would whisper to us. They were always looking for candy or handouts.

“I first drove a jeep and was a chauffeur for a Lieutenant Sears when I arrived in the Philippines. He came down one day and said Cox, and I said, ‘Yes sir?” he said, “You are no longer going to be driving for me.” I said, “what the heck have I done wrong?” “You haven’t done anything wrong, but Major Wills wants you to drive for him,” he said. “I said, me…. Drive for a major?” “My first assignment was to drive him and another major around and we picked up a couple of girls and went somewhere and spent the night,” he laughed. “I was just one of the guys and that Major was a great guy too. I took him and the Lieutenant all over the island for logistical reasons. I don’t know why they selected me but I am glad they did,” HH said smiling. “I guess me being a mechanic probably helped me to get that job.”

HH had a war going on around him and here he is camping out with a couple of majors and two women. He started laughing.

HH recalled a time when he was driving the Major and he told HH to move over he was going to drive. “I had driven to the edge of the Pacific and all of a sudden woke up.” The Major said, “Cox, you are pretty sleepy, ain’t you?” I replied, “yes sir, I sure am.” He replied, “I’m not supposed to, but scoot over and I will drive, you bout run us off into the ocean,” and HH started laughing recalling the story. “I slept with one eye open after that,” he said smiling.

“The day I was ready to go home he and I got into the jeep to another replacement depot. I dropped the major off and when I got back the other guys told me we had orders to go home. We left just before the end of the war and the treaty signed in August of 1945.”

Lettie Cox Clark, HH’s daughter

Lettie said, “Daddy never talked about his service except one time I took him to the doctor and daddy described how he felt when he saw one of his friends get “Gut shot.”

“We were pushing to the front and we were coming down a hill on the other side of the mountain,” recalled HH. “I had my M1 Grand rifle to my side. You could see the enemy running. There were a lot of Japanese running. We called them “GOOKS.” They were running from one side of the hill to the other. We came to the top of the hill and one guy he walked down to the edge of the hill and was hit by a boobie trap. We had to go down and get him the next day. He was killed by the boobie trap.” HH slowly lowered his head and just stared at the carpet. I knew this was very tough for him to recall. Seventy-five years is a long time to hold the horrors of war inside and to ask a veteran to talk about it, is very difficult. “Two boys I went in with,” and HH stopped and again looked down at the carpet.” I didn’t have to press him. I knew what happened to his friends. After a long pause he continued. “One guy I can’t remember his name. He was from East Texas. He was shot right here.” HH pointed to his stomach and ran his finger across. “He looked up at us and said, “Well, ya’ll make the best of it, and he died. I met him on the ship over and we had become good friends. Both of us were from East Texas. He was a jovial kind of guy. I remembered him telling me about farming and his family had a four-team mule not far from where we lived in East Texas. After that, I didn’t have a whole lot to say or talk about.”

HH pressed on, “We were taking the last hill and I got shot. I don’t remember where but I was hit by shrapnel. It was the end of the war for me.

I never held any animosity towards the Japanese, even after the war. They had a job to do just like us. There was this boy, on the last hill we captured as a POW. He had a picture in his hand. A picture of his momma or sister, I don’t remember which. He kept rubbing the picture and looking at me. “My sister, my momma he said over and over. You are not gonna kill my momma and sister?,” “No, we ain’t gonna kill anybody” I said. “He thought we were going to hunt them down and kill them.

HH received a Purple Heart for his wounds sustained fighting at Luzon on the 16th of July, 1945. On the way home, he sent his mother a letter letting her know he was heading home.

The letter read, “To my darling loving sweet mother. I don’t think that I can make it by Christmas, but maybe this will so you can have this where you can see it and think that I will be home in a few days for good. Be sweet, your darling. Love Cpl. HH.”

HH received decorations and citations from the Asiatic Pacific Theater Ribbon, Philippine Liberation Ribbon, Good Conduct Medal, Purple Heart Medal and Victory Medals.

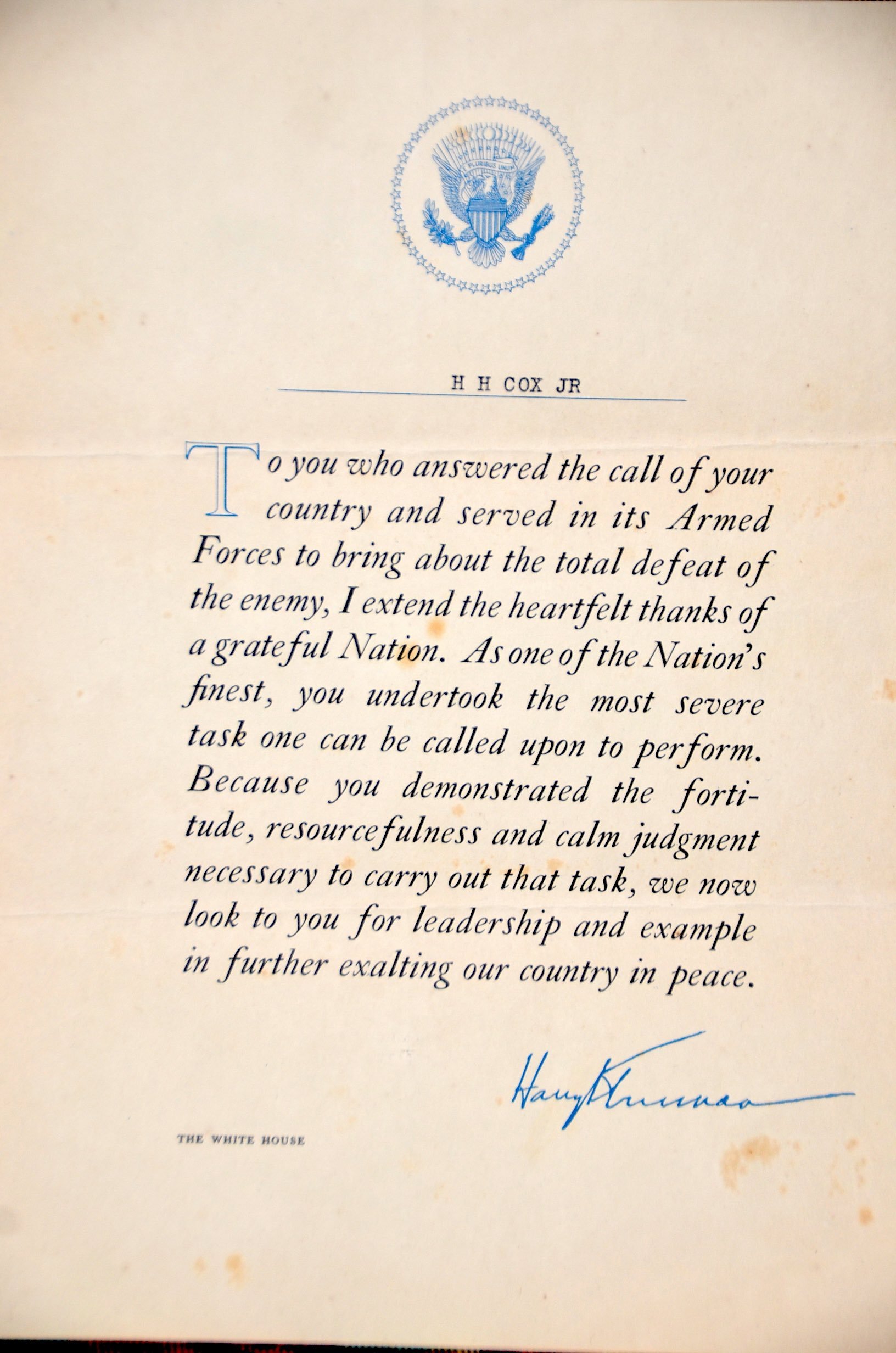

One of the prized letters he received was from President Harry Truman. It read, to HH Cox Jr, “To you who answered the call of your country and served in its Armed forces to bring about the total defeat of the enemy, I extend the heartfelt thanks of a grateful Nation. As one of the Nation’s finest, you undertook the most severe task one cane be called upon to perform. Because you demonstrated the fortitude, resourcefulness and calm judgment necessary to carry out that task, we now look to you for leadership and example in further exalting our country in peace.” Signed Harry Truman

“I was only in the military a little over one year,” said HH. “What did you like about the military?” I asked HH. “NOTHING,” he shot back as he started laughing. “I remembered when they signed the treaty in 1945. I was glad it was over with,” he said.

“I received my honorable discharge at Fort Bliss, Texas on January 12th, 1946,” he said. “If I had to do it all over again, I would still go, I guess I would,” HH said with a prideful voice. “I didn’t have a big part to play in it, but I did enough to know what the boys went thru, and they went thru a lot,” he said. “Lord, my heart…. my heart goes out to them…”

and the tears started welling up in his eyes and there was a long pause.

“Mamma used to tell us when we were young that when there was a noise daddy would jump out of that bed and was prepared,” said Lettie. “He was ready for hand to hand combat,” she said. “He was that way for years when he came back.”

Veterans like HH are what many of us say are a “forgotten generation.” They grew up during the depression and understand a hard work ethic. To them, it was a job and they served bravely and with honor. I am humbled to hear HH share his story with me and understand the sacrifices he has made for this country.

Coming Home

After discharge HH went back home to Kaufman County. His parents still had the farm but he was too sick to help. He had caught fever a week after returning home. HH struggled with a bug he had brought back from overseas. “I was laid up for a long period of time,” he said.

“Eventually I got my strength back and got a job working for Murray Gin in Dallas. I built and worked on Cotton Gins,” said HH. “A cousin helped me get the job. I was getting $.55 cents an hour,” he recalled. “That was more than the military,” I said, and we both got a laugh out of that statement. “I worked there for 26 years,” he said. “I did the foundry work on the Gins. I did a little bit of everything there. We also worked on parts from other Gin Manufacturers including the one in South Dallas,” he said.

“While he worked at the Gin during the day he also worked part time at night at Uncle Amber’s service station at Main and Galloway in Mesquite,” said Lettie. “He worked there for 20 years, holding down two jobs.” “In those days we checked your oil, washed your windshield and pumped your gas,” laughed HH. “I had to make money to raise my five boys and two daughters.”

“Murry’s sold out and all the people lost their retirement,” said his daughter Lettie. “Daddy then went to work for Coca Cola.”

“I worked in Shipping and Receiving,” said HH. “I ended working ten years at the Bottling Plant. My wife was still working at the Levine’s Department Store,” he said.

HH moved to Canton and Van Zandt County in 1984. His wife loved to garden and there was plenty of room in the back for her. She loved living in the country. He was now retired from Coca Cola. He worked in the garden and they loved to go to garage sales and flea markets. He has a garage full of tools. HH was always tinkering on things. “Moma was the boss of the garden and she told me what to do and I did it,” he said laughing.

“Daddy was always laughing and having fun,” said his daughter Lettie. “I never heard him or momma ever say an unkind word about anybody. He never discussed the war in front of me or with me. I have learned more today than I have ever heard. It is just not something where he ever felt free. I have always been proud of him. My dad and mom had a set of rules to live by. They were called the “Hazel and HH Cox FAMILY RULES TO LIVE BY.” Some of them are, “Those that need loving the most, usually by human standards, deserve it the least. Another one, there are always three sides to every story, one side, the other side and the truth. Those are all values we have passed down to our kids.

HH, what is your secret to long life? “Daddy was 81 and momma was 93 and I say treat everybody the way you would like for them to treat you. I have worked hard but I have enjoyed it”

“Daddy mentioned that he didn’t think that what he did was significant during the war. Everybody did the job they were asked to do. That is what won the war. It didn’t matter if you were on the front line or if you were driving around a Major, each of our soldiers did their jobs…..and they did them well,” said Lettie.

HH, you served your country with honor and bravery. You may tell us you didn’t do much…. You were on the front lines of a very terrible war. You did your job. You served and survived and we honor you and say, Thank you.

NOTE: Meet other Veterans from Van Zandt County by going to the top of www.vzcm webpage and click on MEET OUR VETERANS and click one of the (5) branches of services and the veterans last name first and click to read.

“Every Veteran has a story to tell.” Phil Smith

GOD BLESS OUR VETERANS AND GOD BLESS AMERICA

(ALL photos on this Facebook page are ©2020, Phil Smith and Van Zandt County Veterans Memorial. NO unauthorized use without permission) All Rights Reserved.